Straker Translations Ltd (ASX: STG) listed with little fanfare in late October last year – essentially midway through the grinding Risk Off phase that impacted the Growth sector between the end of August and the Christmas period of 2018 (during which time many growth stocks were down 20-40% from their August highs). Floated at a price of $1.51 per share, the company debuted relatively strongly and reached a peak of $1.91 in the first few days of trading – but has spent the majority of the period since trading underwater versus its IPO price, and bottomed out below $1.20 in April – before recovering over the past couple of months (closing at $1.55 on Friday).

Straker recently reported its maiden set of full year results as a listed company (for FY19 – like many Kiwi companies, Straker is a March year-end). We’ll focus on the financials later, but first some background on the company and the language translation market in which it operates.

I’ve seen comparisons between Straker and high-flying Appen (ASX: APX), covered here previously. While there are some similarities, in my view Straker is much closer to what Appen was in its earlier days, before Appen moved so successfully into providing training data sets for the large technology giants and their Machine Learning (“ML”) programs.

Company background

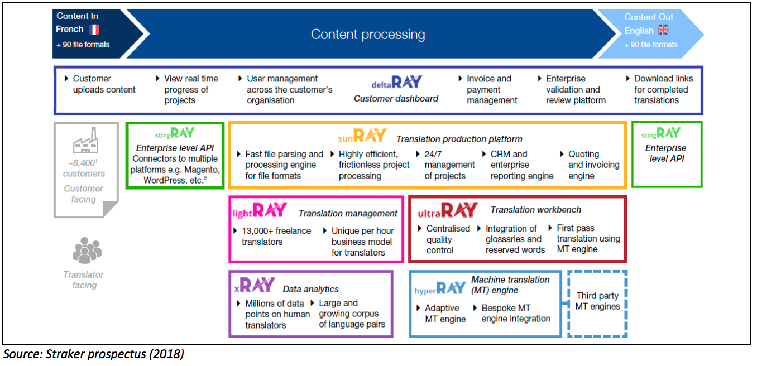

Straker is a cloud-based end-to-end language translation services platform which uses a combination of Machine Learning (“ML”)-based machine translation and a crowd-sourced pool of freelance translators. The company was founded in 1999 and for the first decade of its life Straker provided a multilingual content management platform – before deciding to develop its own proprietary RAY Translation Platform in response to the inefficiencies management perceived in the third party translation services it had been using. Development of the RAY platform commenced in 2010 and the company pivoted to focus on translation services in 2011. The RAY platform took 8 years to develop and per the graphic below from Straker’s prospectus comprises 7 modules (3 customer-facing and 4 translator-facing – which enable fast collaboration between all stakeholders):

The RAY platform creates a first draft translation based leveraging ML techniques and based on previously translated work. As to be expected with ML algorithms, the more translating the RAY platform does, the better the algorithms can become, and the more accurate the first draft is. That first draft is then passed onto one of Straker’s contracted workforce of ~13,000 crowd-sourced human translators for review and refinement as necessary, until the translation is completed and passed to the customer.

Straker charges the many of its customers on a per word basis, whereas it pays its human translators on an hourly rate (around US$30 per hour). This differs from some competitors, which Straker says pay translators by the word. This business model allows Straker to profit if the company can provide translators more efficient ML algorithms, and translation platforms.

Target market and customer base

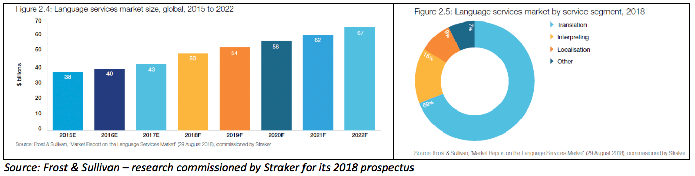

The global language services market was approximately US$50 billion in size at the end of 2018 per Frost & Sullivan, and is projected to increase by 34% to $67 billion by the end of 2022. Language translation (the space in which Straker plays) represents by far the largest segment of the market (~$35 billion in its own right in 2018).

This market growth should provide a tailwind for Straker. We note:

- The continuing decades-long trend towards globalisation, with increasing exports and the need to translate into multiple languages to effect trade, and the continuing rise in e-commerce volumes;

- The growing proportion of global trade comprised by emerging markets which naturally have their own languages (i.e. Indonesia, Vietnam);

- The explosion in online (especially) and offline content – with the Straker prospectus quoting a predicted tripling of IP traffic between 2016 and 2021; and

- Continued regulatory requirements for translations – especially in the EU zone.

As we’ll focus on in the next section, Straker has made a number of acquisitions over the past few years. As such, its customer base includes customers acquired through this M&A activity, ranging from individuals/sole traders needing language translations for a single transaction to large “blue chip” companies requiring a mix of recurring and one-off work. Notable larger clients include IBM, Microsoft, Sony, Universal, Linked In, Deutsche Bank, HSBC, Macquarie Bank, Amazon, Mars and Walmart. In FY18 Straker provided services to ~8,400 customers globally, with the largest customer comprising ~11% of revenue and the top 20 customers approximately 54%. In FY19 the company generated 52% of total revenue from Europe, the Middle East and Africa (“EMEA”), 34% from North America, and the remaining 14% from Asia Pacific (including Australia & NZ). This is a truly global company.

The competitive environment and Straker’s acquisition strategy

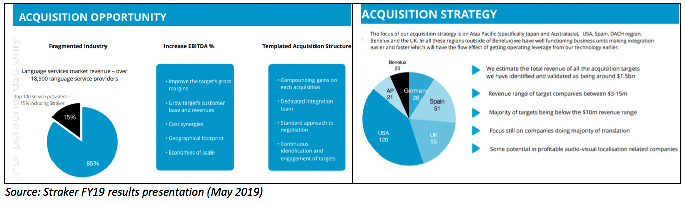

Straker’s prospectus and investor presentations focus heavily on the company’s acquisition strategy – which is arguably the key plank of its overall medium term growth strategy. In a conversation that Claude had with the CEO recently, he revealed that customers tend to be very “sticky” and therefore difficult to win away from incumbent providers. That suggests that the main path to grow market share open to Straker is to acquire smaller rivals…. and there is an awful lot of them, as can be seen from the pie chart in the page bottom left.

Since the market is extremely fragmented, with the top 100 language service providers (including Straker) comprising just 15% of the market and an estimated 18,500 players in total, there is plenty of room for consolidation. But profitable roll-ups must add value, and so this opportunity must combine with discipline and the provision of a superior translation platform. One potential weakness here is that larger customers often have significant negotiation power, and so can sign per-hour translation deals with Straker, thus ensuring that they benefit from any technological improvement.

Most of Straker’s larger peers are domiciled in the US and these are all private: TransPerfect, Mission Essential Personnel, Global Linguist Solutions, LanguageLine Solutions, and Lionbridge (owned by Blackstone, which appointed brokers in December last year for a potential 2019 ASX IPO). By number however, most of Straker’s rivals are located in Europe – where approximately 56% of all players are located, and this makes sense when you consider the large number of languages concentrated in such a comparatively small geographic area.

There are arguably few barriers to entry for a new player into the localised language services market – especially with the sheer number of small existing operators which could be acquired relatively cheaply, but a new entrant wanting to provide ML-enhanced translation services to global enterprise customers would need to develop/acquire their own technology platform, build/acquire their own large data repository to enable accurate and efficient ML processing, and also pool together a global base of human translators.

The Straker prospectus mentions a global translator pool of 333,000 people in 2012 – approximately 78% (260,000) of which are freelancers – which doesn’t sound like a huge number, and given the explosion in language translation apps such as SayHi, iTranslate, Google Translate, Trip Lingo and many others, it’s possible that the global human pool may shrink over time. What level of threat these translation apps constitute to Straker’s offering is yet to be determined – presumably these programs are more conversational in nature as opposed to being suitable for official business translation, but that may change in the medium term. Ultimately, the main difference is quality assurance – we’re not yet at the stage where we can be confident in machine translation without human oversight.

Straker aims to deploy a disciplined acquisition strategy that involves:

- Acquiring smaller companies at a low multiple of revenue (typically at 1.0x or below);

- Migrating the target’s volumes and customers onto Straker’s platform – at which point the company can generate operating efficiencies (and margin improvement) from its ML-based RAY technology;

- Removing cost duplications via the use of Straker’s global back office tech infrastructure; and

- Generating economies of scale in global production capacity and translator resources.

On a pessimistic view of it this is a garden variety roll-up strategy via which Straker aims to generate shareholder value through the smart use of capital and effective integration, though Straker is smart to target specific acquisitions that can bring in attractive new customers or enable expansion of its global footprint. The CEO has said to Claude that the primary purpose of acquiring is to get a foot in the door of large enterprise clients. He said in large organisations, it can be difficult to identify who owns the decision about where to procure translation services, so direct sales can be expensive.

Historically, Straker has focused on companies with $2-3M of revenue with 20-30 employees and limited technological capability (which enables the smooth transfer onto its RAY platform). At these revenue levels, these sub-scale targets are at best only slightly profitable on a reported (pre-synergy) basis.

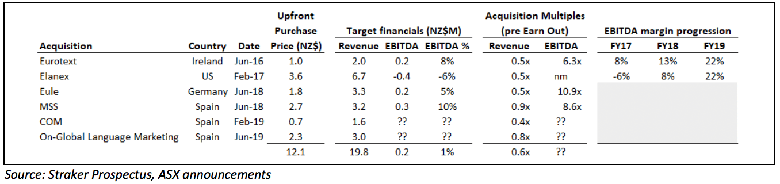

To date Straker has acquired 6 companies (detailed below), with the latest announced yesterday morning. Deals are typically structured around a mix of ~40-60% cash and/or scrip upfront plus an earn-out based on the next 2 years of revenue. The company has provided information to demonstrate the meaningful lift in margins for Eurotext and Elanex following migration onto the Straker platform. Note that the other 4 acquisitions have all been undertaken within the past year and it’s too early to assess margin uplift.

Per the graphic in the previous table above right, Straker is now setting its sights on bolting on slightly larger companies of $3-15M revenue – no doubt as a result of the $20M raised in the IPO last year.

On the FY19 results investor call management re-iterated that it is very active in hunting acquisition targets that meet its criteria and financial hurdles, and indeed it subsequently announced the acquisition of On-Global Language Marketing for less than 1x revenue. This is its third Spanish acquisition and it is seeking a meaningful acquisition into the US which would deliver an existing enterprise customer base.

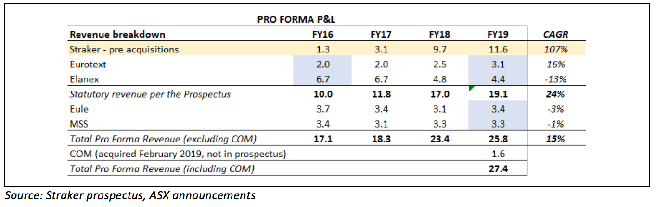

The key question for me from all of this is the breakdown of organic vs. inorganic (i.e. acquired) growth in the historical numbers, and what we can expect for organic growth going forward – remembering that Frost & Sullivan’s target market growth projections presented earlier estimate annual growth in excess of 7%. Straker’s investor presentations want us to focus on pro forma revenue – that is, as if all 5 acquisitions had been undertaken at the start of the period. The below table summarises information from the prospectus and different investor presentations in April and May 2019 (and excludes the COM acquisition made at the end of FY19). Notable here is the winding down of some key contracts in the Elanex business which was known prior to acquisition by Straker.

Please note, the above table does not represent statutory results for FY 2016 and FY 2017 but it is simply trying to split out acquired vs organic growth. For illustrative purposes, I’ve pushed Eurotext’s and Elanex’s FY17 revenues back into FY16, which may not be accurate. This analysis is likely distorted by what I believe is the migration of some acquired volumes to the “Straker – pre acquisitions” line – which is growing considerably faster than the acquired businesses (as reported separately by Straker). In the absence of any breakdown of FY19 revenue by business unit, I’ve apportioned the $0.9M revenue beat versus prospectus forecasts between all businesses on a weighted average basis (using the FY19F numbers from the prospectus). Given the likely migration of volumes within the group, this analysis unhelpfully doesn’t help definitively answer the organic-vs-inorganic growth question – although it’s likely the core (excluding acquisitions) Straker business is generating decent (at least) organic growth. This may be direct sales resources are focussed disproportionately on the Straker brand.

Further, it’s still evident that even on a pro forma basis, the group has increased revenue at a CAGR of 15% between FY16 and FY19 – faster than the market, which is important to note in my view. Management stated on the FY19 results investor call that 2H19 organic growth was ~9% on a constant currency basis (down from 14% in 1H19).

Aside from inorganically acquiring smaller rivals, Straker’s organic strategy revolves around:

- Winning new enterprise customers with recurring volumes – via a new direct salesforce established over 2018/2019 comprising 16 salespeople in 7 countries;

- Expanding volumes with existing enterprise customers;

- Integrating the RAY platform with popular content and eCommerce platforms such as Wordpress, Adobe and Magneto; and

- Expanding transactional (i.e. non-recurring) volumes as a means to provide cashflow (as the majority of transactional revenue is paid upfront) and soak up excess capacity amongst its translator pool.

Financials

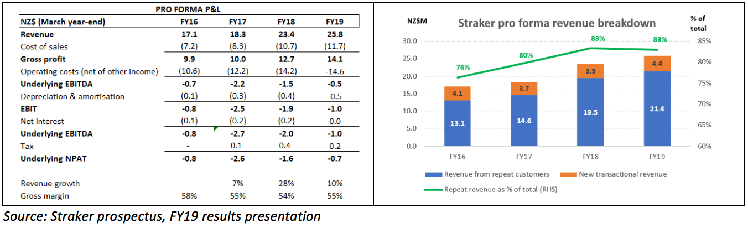

Straker’s historical financial performance is detailed below left. Note that this is on a pro forma basis – as if the first 4 acquisitions had all been completed prior to FY16 (and so excludes the recent COM acquisition) and differs from statutory reported results. Gross margins are healthy at ~55% and one would hope that margins will increase as the ML algorithm becomes more efficient and accurate. As can be seen from the chart below right, the company generated ~83% of its revenue from repeat customers in FY18 (including enterprise Master Service Agreements), an increase from 76% in FY16 and a pleasing upward trend.

The company recorded a slight beat versus prospectus forecasts at an underlying EBITDA (+$0.1M EBITDA) on a $0.9M pro forma revenue beat. Management did not provide any FY20 guidance (steadfastly refusing on the results investor call) – primarily due to the recent COM acquisition presumably – but we’d hope that some FY20YTD progress at least (if not actual FY20 guidance) is provided at the upcoming AGM.

Straker is reaching its EBITDA and cashflow breakeven inflection point around about now (after being cashflow neutral over the last two quarters combined), and as such there should be a reasonable amount of inherent operating leverage as additional translation volumes are added to the platform. Management want us to use Eurotext and Elanex (the first 2 acquisitions) as examples of the kind of operational improvements that the company is able to achieve post acquisition – and both of these businesses were generating 22% EBITDA margins within 2 years, suggesting that there should be some meaningful earnings uplift as the company continues on its acquisition path.

Closing thoughts

It needs to be noted that Straker’s future growth prospects rely heavily on the future acquisition pipeline (both the quality of these targets and management’s success in post-acquisition integration). The language services market is extremely fragmented and there is absolutely a consolidation opportunity available to the company (and ~NZ$18M of cash to fund this at the end of March).

It also needs to be remembered however that roll-up plays don’t always go according to plan (as shareholders in Paragon Care, National Veterinary Care, G8 Education and most recently Think Childcare (with its incubator tipped into administration last week) would lament). While Straker is keen to communicate that its acquisition and integration process is proven and repeatable, the company has finalised only 2 integrations to date, with operating synergies from the other 4 acquisitions yet to be fully realised.

At a $100M market cap (on a fully diluted basis) and a reasonable line of sight on the medium term growth trajectory – albeit dependent on the number and size of bolt-on acquisitions not yet initiated – Straker is not overly expensive at current levels, though it will need to grow earnings materially over the next year or two to grow into its current valuation given it’s only tipping into break even territory presently. The key is that the company is able to improve margins in acquired company through the provision of superior technology. Even then, it’s possible that margins will be competed away longer term, so we believe that the company must reach and maintain positive free cash flow (excluding acquisitions) if is to demonstrate a viable growth model.

While I am generally positive about its prospects, I consider it a relatively lower conviction holding for me personally at this stage, and am waiting for FY20 guidance which will hopefully be provided at the upcoming AGM before adjusting my own personal view. Finally, unlike the doubling of other Ethical companies Audinate and Appen in the past year for example, I feel that Straker is likely to be a slower burn from a share price appreciation point of view – unless the company supercharges its growth ambitions by undertaking the acquisition of a $10-15M revenue target (although that require a higher multiple paid by Straker and an associated capital raising). Industry organic growth of 7-10% is nothing to sneeze at – but personally I feel that Straker is unlikely to end up commanding premium multiples like Appen over the medium to longer term.

_______

A note from Claude:

I contributed to this report and I agree with its contents. For me, it is extremely important that the company prove it can make a profit and generate a positive free cash flow yield. If it can, then it could use its current cash-hoard to fuel revenue, margin and profit improvements until it has enough free cash flow to fund further acquisitions. Should this virtuous fly-wheel gain momentum, then I believe it will be impressive to watch. However, my entire thesis relies on this fly-wheel of self-funding growth and I have no interest in investing in “multiple arbitrage” roll-ups. I’ll sell without warning if I decide Straker is in the latter camp, but not for at least 2 days after the publication of this article (obviously).

Disclosure: Both Fabregasto (the author) and Claude Walker own positions in Straker and will not trade STG shares for at least 2 days after the publication of this article.

For early access to our content, join the Ethical Equities Newsletter.

Ethical Equities is currently underfunded. If you don't yet use Sharesight, please consider signing up for a free trial on this link, and we will get a small contribution if you do decide to use the service (which in turn should save you money with your accountant, or time if you do your own tax.) Better yet, you can get 2 months free added to an annual subscription.

This article does not take into account your individual circumstances and contains general investment advice only (under AFSL 501223). Authorised by Claude Walker.